So after the death, the post-mortem. As the results of the PCCs elections emerged today, the sheer scale of the embarrassment became apparent to even the most ardent government supporter. The Electoral Commission promised to investigate the worst election turnout in the post-war period. Highlights included one polling station where literally no-one voted and, nearer to home, 10 times the usual number of spoiled ballots (ahem) in the neighbouring county of Suffolk. Opponents blamed a lack of information and publicity, those sympathetic to the cause suggested the weather. The government adopted its favourite passive-aggressive tactic of blaming a lack of understanding by the electorate, like with the earlier NHS reforms, further cementing an unfortunate reputation for condescension.

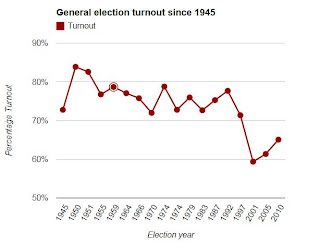

But even for an opponent of the measures like me, I can see this is not an isolated case, but part of a trend that worries a lot of people. Although we expect minor ballots, like yesterday's, to attract low numbers, long term trends show falling levels of participation in even General Elections, which usually attract the highest numbers of voters:

So what does this mean? Are fewer of us interested in politics than previous generations? Have politicians so betrayed our trust that we are punishing them by not turning up at the polls? Or is this symptomatic of loosening social ties - where there is no sense of duty to vote, and no social embarrassment in not voting? Actually, I think it's much simpler than that - elections haven't caught up with our entitlement to choice.

Choice, as a political concept, has been a watchword of the Right for at least 30 years, and is now grudgingly embraced by the Left when the occasion suits. At its worst, it's an excuse for dismantling public services, whether through ideological zeal or economic necessity. At its best it allows us to demand more from the world around us, and often the world responds to that need. I can remember when, in order to get a telephone, you had to register with British Telecom, rent a phone from them, and then wait 6 weeks before they bothered to come around to connect you. That seems as alien from today's world as motor cars must have been to the mid-Victorians.

The diversification of services, growth of choice, and speed of technological change has not only revolutionised our lives, it has fragmented what were once collective experiences. If the War represented a Year Zero in collective experience - rationing, mobilisation, isolation - then the 70 years since have been an ever-widening funnel of disparate and diverse possibilities in an integrated world. People talk with glassy-eyed fondness of the days when 25 million Britons would watch Morecambe and Wise at Christmas, conveniently forgetting that this was largely because there were only 3 TV channels to watch. Even in my youth, in playground reenactments, I could pretty much guarantee my friends would have watched the same TV show the night before. Now, it could be from any one of hundreds of channels, assuming they watched anything at all, and weren't on an XBox, Facebook or uploading themselves singing onto YouTube.

And yet, come election time, we expect everyone to suddenly act like a homogenous group: to do the same thing on the same day in a way that would be familiar to their grandparents. While we have crawled with the times to allow postal voting for those cheeky enough to go on holiday during an election, it is a remarkably old-fashioned demand to make of generations who have been told they can have what they want, when they want. Pause the TV, buy it online, listen to it whenever you want, speak instantly with your friends any time of day. It's not that people don't take an interest any more, but that, frankly, it's not that convenient, and we've been told choice is not just good, it's practically a human right.

But it's more than thinking up radical solutions, like voting with your iPhone, or gamifying voter participation. People don't just expect the world to work to their pace, there is more competition for their time. Or, to put it simply, there's more stuff to do these days than 30 years ago. Politicians who worry about these trends think in terms of making politics "fun" and "exciting", as if anyone other than policy wonks has ever felt that way about it, even in the 1960s. But 50 years ago, there was less to distract you, less to do. The pubs closed every time you felt thirsty, you might as well go and vote. Now, we can do all the same things people did then as well as everything else that's been invented since - basejumping, web-surfing, battle reenactments, 24-hour drinking, gambling, TV on demand, skateboarding, night-time shopping, Gangnam-style dancing. You can do stuff whenever you want - it is utterly amazing and thrilling. Except vote. You've got to queue in the pissing-down rain, to mark a scrap of paper with a scratchy pencil on a string at the local church hall on one day of the year, outside of work, childcare, parent-care or anything else you might do. Frankly, given the choice between a session of Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 or picking between three charmless greasers you'll never see for four years, I'm surprised they even get 50%.

Check you’ve got the latest version of FishBarrel ready for the Nightingale

Collaboration’s next campaign

-

The Nightingale Collaboration will shortly be launching a new and exciting

campaign that you can help out with – but you’ll need to make sure that:

- ...

12 years ago